フリクリ.

aka Furi Kuri.

Or Fooly Cooly.

Or just FLCL.

“What’s it about?”

“Well…there’s a boy. And he gets run over by this alien girl on a yellow Vespa. Then she whacks him in the head with her blue Rickenbacker bass guitar, which causes a horn to grow from his forehead. Then later, two giant robots come out of his horn and start fighting each other, and then the winner starts working at the boy’s family’s bakery.”

“…Uhh..”

“Oh, and..it’s a coming-of-age story.”

“……Huh?”

I’ve always enjoyed observing the puzzled expressions on peoples’ faces whenever I get a chance to talk about FLCL, a bizarre six-episode Japanese animated mini-series from the year 2000–directed by Kazuya Tsurumaki. Sure, it’s a tad unfair to just rattle off the events of the first episode with zero context, but it also seems to be one of the more effective ways to get people interested in this show. Well, more effective at least than offering a vague plot synopsis and saying something generic, like the fact that it’s “every bit as deep and complex” as it is “nonsensical and surreal” (which I’ll get into later).

But what is FLCL really about? How and why was it made? What are its influences? And who is the nutcase who came up with it?

Welcome back to CONTEXTUALIZED, where I’ll be investigating the who, what, when, how, and why of FLCL’s production. In my experience, “contextualizing” like this always makes great works better and the appreciation bigger.

From the start, Kazuya Tsurumaki wanted his directorial debut to be something different. He wanted it to be both accessible to casual animation fans and layered with visual concepts ripe for analysis and interpretation. But above all, he just wanted it to be fun, and something only HE could have made.

Born in the year 1966, Tsurumaki grew up in the city of Gosen, Japan–a city known for its tulips, hot springs, and not much else. He spent his early twenties doing key animation for such shows as 1986’s Galaxy High School and 1988’s Maison Ikkoku before landing a job at famed animation studio Gainax, which would shape the rest of his career. He started as a key animator on Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water and quickly proved himself to Gainax’s leaders, including director Hideaki Anno, who hired Tsurumaki as his assistant director on his landmark psychological mind-f*ck mecha series Neon Genesis Evangelion, where he eventually worked his way to become co-director of the series finale, End of Evangelion.

Left: Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995 TV series). Right: End of Evangelion.

“Tsurumaki is next,” Anno declared after completing Evangelion in 1997. It was time for Tsurumaki to make his solo directorial debut. He started right away planning and generating ideas for the project, but a year later, he couldn’t settle on anything. So the studio started work on another project: the romantic comedy Kare Kano, from 1998 to 1999. After that was wrapped up, Tsurumaki got back to work on his own project, this time buckling down and finalizing his ideas. “I knew you couldn’t start production whilst worrying,” he reflected during an interview with Japanese site Mynavi News, “So I decided to start off by thinking about the troublesome parts I liked, and not thinking about the troublesome parts I didn’t like.”

“There were times in the planning when things weren’t going smoothly,” said Tsurumaki at Anime Expo 2016, “Anno told me that you don’t have to make something perfect that everyone will love – just do what you want to create.” From the beginning, Tsurumaki always wanted his project to “have a different flavor…Evangelion was so somber, I wanted this to be wacky and outrageous,” he stated at Otakon 2001.

Tsurumaki was told by the Gainax heads that he could do whatever he wanted with the show, so he made sure to plop in some of his favorite things, including giant robots, cats, baseball, vintage guitars, and bikes. “I was very lucky in that respect, because that’s just the kind of organization Gainax is. If it had been some conservative studio I was with, FLCL would never have been any more than an idea,” Tsurumaki reflected.

In fact, many of FLCL’s most iconic elements were merely things Tsurumaki was fond of in real life. For example, Tsurumaki apparently always admired the Italian Vespa motor scooter owned by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto–one of Gainax’s founders and its lead character designer–but could never come up with a good enough of reason to buy one himself. Until he thought: if he could use it as a prop in his series, that would be a solid excuse.

Thus became FLCL’s iconic yellow Vespa.

Tsurumaki was also thinking about the music in his series. The Pillows were a very unknown yet prolific Japanese alternative rock band formed in 1989; and in 1999, they were discovered by a director making a very alternative show. “Normally, anime uses background music that’s classical—strings, pianos. I don’t listen to that—I like electric guitars, drum sets; i.e., bands. Now, I thought, is there some reason they don’t use bands on anime soundtracks? I thought I’d give it a try and see if it worked out for my show. The Pillows are my favorite band, so even before we started production, I contacted them and asked if we could use their music. And they were very willing.”

Thus became FLCL’s iconic soundtrack. (listen to one track below)

And of course, the title–where did that come from? According to the man himself, the idea came from a music magazine with a CD titled “Furikuri.” Tsurumaki loved the onomatopoeia-like sounds from Japanese-abbreviated English phrases, like “Pokémon” for “Pocket Monsters” or “Buri-Guri” for “Brilliant Green” (a J-pop band).

Thus became Furi Kuri / Fooly Cooly / FLCL.

So, what is FLCL about? Well, it certainly is both “wacky” and “outrageous.” Tsurumaki himself described it** as “full of nonsense. It’s a boy-meets-girl story, but the boy gets run over and hit by her guitar.” It stars a 12 year old boy named Naota Nandaba, who is already sick of life in his small hometown. All he wants to do is be an adult, and when all the adults around him act like children, he doesn’t find it particularly challenging. That is, until intergalactic police investigator Haruko Haruhara literally crashes into his life and forces him to shatter his cocky attitude and learn the truth about growing up.

**From the FLCL DVD Director’s Commentary

In the year 2000, FLCL was officially released straight-to-video in Japan as an OVA (Original Video Animation) across six separate DVD sets, each holding a single episode. Unfortunately, it didn’t reach a huge domestic audience. But in 2001, the (now defunct) U.S. anime-licensing company Synch-Point acquired FLCL for home release in the States; and in 2002, Cartoon Network acquired FLCL for broadcast on its Adult Swim programming block.

A 2003 Adult Swim bumper.

The August 2003 television premiere drew in a surprising amount of views, as did the entire series as it aired midnights on Mondays through Thursdays. On August 12, 2003, FLCL was “ranked No. 42 among all shows on ad-supported cable among adults 18–34.” Its modest, yet surprising success on TV and on DVD brought it to cult-hit status across the west, prompting Adult Swim to broadcast reruns several times between 2003 and 2011, again in 2013 as part of the revival of the Toonami programming block, and once again in 2018 leading up to the premiere of the long-awaited sequel series FLCL Progressive in June.

FLCL also inspired many people working in western animation, most notably influencing such shows as Teen Titans, Steven Universe, and Avatar: The Last Airbender. Avatar episode director Giancarlo Volpe has even admitted that the staff “were all ordered to buy FLCL and watch every single episode of it.”

So, what makes FLCL so popular? What are its influences?

Let’s dive in. Spoilers Abound.

EPISODE 1 – “FURI KURI” / “FOOLY COOLY”

Right off the bat, episode one–titled “Fooly Cooly”–introduces us to the voice of Mamimi Samejima, a high school girl. We listen to her misquoting boxing tips from the manga Ashita no Joe as baseball advice for elementary school student Naota, who is busily doing his homework. Although he is barely listening to her, he is quick to point out an error in her hand placement on his baseball bat. Both he and Mamimi are right-handed. Mamimi drops the bat and begins to embrace and caress Naota from behind. Naota doesn’t stop her, but he doesn’t let himself be happy, either. Of course, the difference in their ages gives us an uncomfortable feeling about their relationship. Mamimi offers Naota a sour lemon drink, and he vehemently refuses, whining, “You know I don’t like sour drinks!”

Naota and Mamimi.

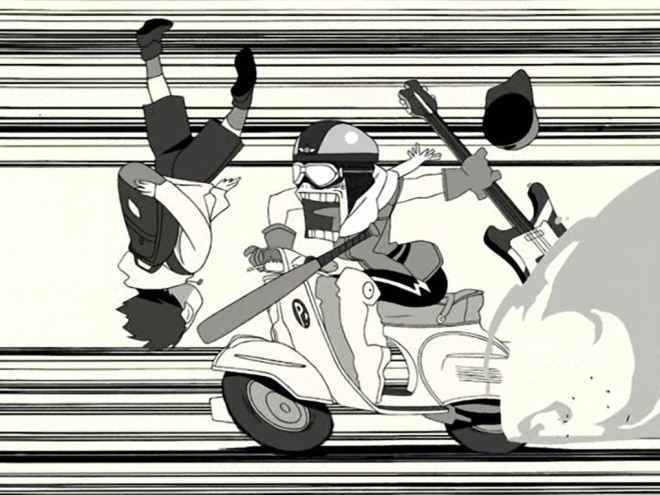

After the title sequence, Naota tries to tell Mamimi about his older brother’s whereabouts (her ex-boyfriend, whom she is still in love with) when he is violently interrupted by a pink-haired, yellow Vespa-riding, blue bass guitar-wielding girl who runs him over, then thrashes him over the head with her guitar. Haruko Haruhara, as we come to know her, is left-handed.

From the beginning, Tsurumaki wanted to make clear distinctions between two different types of characters***. The first way he makes this distinction is by the characters’ handedness: Naota and Mamimi are both right-handed; they are both deeply flawed and still have a lot of room to grow and mature. Haruko and Naota’s brother Tasuku (whom we never meet) are left-handed; they are both naturally gifted, independent, carefree, and cool. The director, Tsurumaki, is right-handed like Naota and Mamimi.

(***Note: Much of the following behind-the-scenes information and insight from Tsurumaki was pulled from the FLCL DVD Director’s Commentary)

When designing the character of Haruko, Tsurumaki and FLCL screenwriter Yoji Enokido wrote her as “a selfish adult woman who teases Naota,” but when describing her character to other staff members, they would comment “Oh, like Misato [from Evangelion]?” Wanting to avoid comparisons to Evangelion as much as possible, Tsurumaki and Enokido ended up giving Haruko a wild and eccentric personality. They cast Mayumi Shintani (Tsubasa Shibahime in Kare Kano) to play Haruko, because of her unique voice, and further developed the character from there. Haruko’s visual design is partly inspired by the chic style of shoujo manga artist Moyoco Anno (the wife of Hideaki Anno, and friend of Tsurumaki and FLCL’s character designer Yoshiyuki Sadamoto).

Left: Moyoco Anno’s Happy Mania. Right: Haruko, illustrated by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto.

After being hit by Haruko’s guitar, Naota discovers a large horn growing out of his forehead. He hides it with a bandage and heads off to school. It’s interesting to note that the concept of a horn growing out of Naota’s head didn’t come until late into production; originally, Naota just hits his head and starts to feel sick afterwards. But, they realized that they needed something more visually engaging to communicate that feeling. When the notion of a horn was brought up, it met with the approval of the screenwriter, Enokido, who liked the subtle sexual undertone. Tsurumaki explains, “Enokido-san writes lots of those kinds of images. How should I say, sexual images… Because he really likes them…[For FLCL] I wasn’t trying to incorporate as much sexual imagery as possible, but Enokido-san really enjoys them, so he kept putting them in.”

One of the most popular fan theories about FLCL, in fact, is that the story is a metaphor for male puberty. Personally, I’ve always seen FLCL to be about growing up in general with no emphasis on sex, though admittedly some of the sexual imagery and dialogue can be pretty difficult to deny at times. It’s no surprise that the same screenwriter who pulled swords out of girls’ chests as a metaphor for lovemaking in Revolutionary Girl Utena (1997) would also go on to equate horns (and later, guitars) with phalli in FLCL.

Left: Revolutionary Girl Utena. Right: FLCL.

In the hills surrounding Naota’s small city, Mabase, there sits a giant iron-shaped factory –another of FLCL’s most iconic images–owned by an ambiguous organization known as Medical Mechanica. Every now and then it sounds an alarm or releases exorbitant amounts of steam. The idea for a giant iron came from Tsurumaki, who at first thought simply that a big “sci-fi iron” would be a cool visual. But as production went on, the iron was integrated into the show’s themes–the iron’s function of flattening things, as Tsurumaki explains it, represents the goal of “making things the same, making things smooth, getting rid of unevenness…That is, making people like Haruko, with ‘uneven’ personalities ‘smooth’, by making everyone the same. I want the iron to symbolize the power to make everyone boring human beings.”

Even though Naota tries his best to hide the horn growing from his forehead, Haruko, who already knows about it and is very interested in it, begins to stalk and pester him. After escaping from a hospital (owned by Medical Mechanica) in which Haruko disguised herself as a nurse, we go to commercial. Fun fact: FLCL’s commercial break bumpers feature a chorus of voices shouting “Furi Kuri”–these are the Japanese voices of Mamimi, Haruko, and Eri Ninamori (a classmate of Naota we formally meet in episode three).

Happening after the break, possibly the most visually striking scene in the first episode is the dinner sequence where Haruko reveals that she’s Naota’s new roommate and his father’s new housekeeper. The scene is animated entirely in black & white manga format, with the camera simulating a reader’s eye following the panels. The reason this was done was to make a potentially boring two-and-a-half-minutes of the characters talking, exciting. This ended up being incredibly troublesome to pull off; however, as it was impossible to do with traditional hand-drawn cells, and it would take up an enormous amount of memory if done in the computer. Nevertheless, Tsurumaki insisted on its inclusion, and after its completion, the digital artists asked him to never do it again.

Approaching the climax of episode one, Naota runs out of the house one evening to meet a depressed Mamimi, who had just bought a large bag of cheap, day-old bread from Naota’s family’s bakery. Either she’s run from her home, or she’s not welcome at her home. The cigarette she is smoking has the words “Never Knows Best” handwritten on it, reflecting the way “Mamimi has given up on the future,” Tsurumaki hints. The idea for this visual came from a postcard Tsurumaki had with an image of a cigarette with the phrase “Joint London” written on it.

“Never Knows Best”.

When Mamimi begins to cuddle up with Naota again, he stops her and breaks the news he meant to tell her earlier: his brother, who is living in the U.S. now with a baseball scholarship, found himself an American girlfriend. Mamimi starts to feel noxious, and Naota feels a sharp pain in his forehead. His horn breaks free from the bandage and grows to the size of his arm, then two 10-foot tall robots climb out and start clashing, dragging Naota along for the ride.

Naota’s robots face off.

Tsurumaki, according to the DVD director’s commentary, wanted to put robots in the show no matter what, even if it didn’t “make any sense.” Eventually, he came up with the concept of robots coming out of Naota’s head episode-to-episode as a part of the plot. The design for the main robot character (who starts working as a helper at the family bakery at the end of episode one), came about because Tsurumaki didn’t want it to look like a generic “Japanese anime robot.” So, he decided to give Canti–the name given to it by Mamimi in episode two–a square head. And, thinking of ways to make it so it wasn’t a plain cube, Canti’s head eventually became a television set.

Naota narrates the opening and closing of this episode: “Nothing amazing happens here. Everything is ordinary.” On his way to school the next morning, he meets Mamimi, who offers him another can of the same sour lemon drink from the beginning of the episode, but this time, after some hesitation, Naota takes a sip.

And that’s episode one.

Now, I could talk about the remaining five episodes just as in-depth as I did for episode one, but I know many of you haven’t seen this show, and I want to preserve some of the mystery. It’s a pretty quick watch, anyway, at 2.5 hours (the average length of a summer blockbuster). As a teaser, I will divulge that in episode two we learn more about Mamimi’s character and her relationship with Naota, episode three introduces us to Naota’s female counterpart and classmate, and episode four goes extra surreal while developing Naota’s character.

For the rest of you who have seen FLCL already, here are some things to think about on your next viewing, including behind-the-scenes tidbits, fun facts, and some analysis by Tsurumaki himself. (Full disclosure, many of these points are taken from the fascinating FLCL DVD director’s commentary).

EPISODE 2 – “FI STA” / “FIRE STARTER”

- Naota’s cat Miyu-Miyu is voiced by Hideaki Anno, though he is credited as “?”. Mamimi’s cat Takkun, in order to differentiate it from Miyu-Miyu, is drawn very cartoonishly. Takkun the cat is voiced by Naota’s voice actress Jun Mizuki, who was asked to say “na na na…” instead of the typical “meow”–again, to make Takkun different.

Left: Takkun. Right: Miyu-Miyu.

- Speaking of Jun Mizuki, the then 27 year-old voice actress was chosen to play Naota because her voice sounded “intelligent and cool,” even though they originally planned to audition 12-13 year-olds for the role.

- At about 8:44, the animation style changes completely for roughly thirty seconds. This distorted, rotoscope-like style is thanks to key animator Shinya Ohira, who is famous for his work in things like: Akira, Tekkon Kinkreet, Redline, Mind Game, Ping Pong the Animation, several other Masaaki Yuasa projects, several Studio Ghibli projects including Spirited Away and The Wind Rises, as well as The Animatrix: Kid’s Story and the Kill Bill anime sequence. Tsurumaki thought Ohira’s style was strange but very interesting, so he decided to leave his style as-is for the finished scene.

- In the U.S., several murders and other controversial incidents have occurred surrounding deranged Dungeons & Dragons players taking their games too seriously by bringing them into the real world. These incidents gave Tsurumaki the idea for Mamimi’s character in this episode; how she mistakes the TV-robot for the god Canti from the game “Fire Starter” and gets inspired by the game to set fire to buildings in real life.

- Tasuku’s jersey in Mamimi’s flashback has the number “3” printed on it: an allusion to Yomiuri Giants third baseman Shigeo Nagashima, whom Tsurumaki describes as “a baseball god.”

- Fun fact: the evil robot that comes out of Naota’s head in this episode is missing a left arm. In episode one, the evil robot that comes out of Naota’s head is just a left arm.

- Canti has two forms: green and red. Green Canti apparently represents a meek man who takes orders and runs errands. Red Canti, on the other hand, represents “a masculine, strong man…to Naota, that’s his brother,” says Tsurumaki.

- Some fans have gone so far with the connection between red Canti and Tasuku that they have crafted a theory that when Tasuku went to America, he somehow got turned into Canti so he can watch over his little brother. Red Canti even pats Mamimi on her head after saving her, like Tasuku did in Mamimi’s flashback.

EPISODE 3 – “MARU RABA” / “MARQUIS DE CARABAS”

- The title of the episode comes from the European fairy tale The Puss in Boots. In the story, a cat uses lies and trickery against a king in order to bring great fortune and a beautiful wife to his poor master, whom he gives the fictional title of the “Marquis of Carabas.” Naota’s class is putting on an adapted school-play version of the fairy tale in this episode.

- In case you missed it: In episode one, the back of Canti’s head was broken by Haruko’s bass guitar. In episode two, Canti scavenges for the scattered pieces of his head. In this episode we see Canti trying unsuccessfully to glue the pieces together, before Haruko discovers him and offers him a cardboard box to wear instead. As mentioned by Tsurumaki, the FLCL staff thought Canti looked like the famous anime character Sazae-san because of the three open flaps of the cardboard box and his traditional Japanese apron.

Left: Canti. Right: Sazae-san.

- Like his comparison of right-handed characters to left-handed characters, Tsurumaki also makes a similar distinction between people who like spicy food and people who don’t, with people who like spicy food seeming more “carefree” and “cool.” Personally, I find it interesting that Haruko makes it clear that she likes spicy food, Naota makes it clear that he doesn’t, Ninamori tries to like it but ends up not being able to handle it, and in the next episode, Commander Amarao pretends to like it at first, but then we catch him in the midst of dissecting it, and he admits he doesn’t like spicy food after all.

- Random product placement: When Naota walks into his bedroom after Ninamori has finished her bath, he is drinking Weider Vitamin IN health juice. Apparently they were planning to get an official sponsorship from Weider, but by the time they finished the animation for this scene, Weider backed out of the deal.

- Tsurumaki on Ninamori’s rampage: “Ninamori is usually cute, intellectual, and calm, so when she explodes, it’s a huge contrast… People like that are always seriously trying to keep it together. And in the end, it’s scary when they just snap. I wanted to create that feel.”

- The classical music featured in the battle sequence in this episode is the “Comedian’s Galop” from The Comedians Suite, Op. 26 by Dmitry Kabalevsky, which was chosen by Tadashi Hiramatsu, the animation director, who is a big classical music fan. This piece is one of many classical songs often played during Japanese school sports meets.

"Comedian's Galop"

- Fun fact: Printed on Naota’s lunch box is the word “lover” (in Japanese, “raba”) enclosed in a circle (“maru” in Japanese), in reference to the title of the episode, “Maru Raba.” The title, while chiefly being an onomatopoeic abbreviation of “Marquis de Carabas,” is also meant to call to mind the word “lover” (“raba”), hinting at the possible romance between Ninamori and Naota.

- On the meaning of “they’re fake,” the final line of the episode, uttered by Ninamori: “Until now, [Ninamori had] been lying to herself, trying to be a leader and grown-up…Naota does too. But Ninamori has changed from this experience… [She’s learned that] rather than fooling yourself, it’s better to fool others. It’s a little more adult.”

EPISODE 4 – “FURI KIRI” / “FULL SWING”

- It was originally planned to send Naota’s brother Tasuku not to the U.S., but to a Japanese high school with a famous baseball team. Eventually it was decided that sending him to the U.S. made his distance from Naota and Mamimi clearer and it required less explanation.

- Haruko’s baseball uniform is modeled after the uniforms of the real-world Kintetsu Buffaloes team.

Left: Haruko. Right: Kintetsu Buffaloes.

- Commander Amarao is in part inspired by Twin Peaks protagonist Dale Cooper. His name comes from a Brazilian soccer player named Amaral, who once played on the FC Tokyo team in the Japanese Soccer League.

Left: Amarao. Right: Dale Cooper.

- Naota apparently hitting his dad with his baseball bat is inspired by real world incidents in Japan wherein children beat their parents to death with metal bats.

- Miyu-Miyu decapitating a dummy of Haruko “symbolizes Naota’s suspicion of Haruko’s and [his father’s] relationship. Naota’s started to look up to Haruko, but now that it seems that she’s chummy-chummy with his dad, whom he doesn’t respect, her image has been sullied for him,” suggests Tsurumaki.

- The direction for this especially surreal episode is by virtue of animation director Nobutoshi Ogura, who has worked on such films/series as: From the New World, Kare Kano, Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex, Kemonozume, and Mind Game. According to Tsurumaki, Ogura has a passion for 1960s Japanese cinema and enjoys unique artistic expression and complex storytelling.

- When Mamimi shouts “Lord of Fear,” she is referencing the prophecies of Nostradamus, a French physician who lived in the 1500s and predicted the world would end in the year 1999.

- Naota’s guitar, the Gibson Flying V, was originally going to be given to Haruko (Character Designer Yoshiyuki Sadamoto agreed that the Flying V’s dynamic shape would be more iconic), but in the end, Tsurumaki liked the look of the Rickenbacker 4001 bass guitar more, so he gave the Flying V to Naota.

Left: Gibson Flying V guitar. Right: left-handed Rickenbacker 4001 bass.

- Similar to the distinctions between right- and left-handed people, and those who like spicy food and those who don’t, there are the people who swing the bat vs. those who don’t. This whole time, Naota has been scared to know his limits–he’s always carried his baseball bat around, but he’s never swung it once. The way Tsurumaki puts it, Naota has always accepted three “outs.” He believed that as long as he didn’t swing the bat, the possibility was still alive that he COULD hit a home run. He’ll get a strikeout, but at least then, he can pin it on the fact that he didn’t try, NOT that he isn’t skilled (like his brother).

- Tsurumaki on the meaning of Mamimi’s despondent “[Naota]…swung the bat.”: “Mamimi would dote on Naota because he was the kind of guy who wouldn’t swing his bat…but now that he has, Naota is “a bit dangerous” to her. Before, their relationship was controlled by HER, but now that Naota has found his independence, HE has the potential to start controlling their relationship.”

EPISODE 5 – “BURA BURE” / “BRITTLE BULLET”

- Alongside the shameless parody of Lupin the Third, is a reference to John Woo’s films, which always have, Tsurumaki jokes, “meaningless pigeons.” (at around the 00:50 mark)

Left: FLCL. Right: John Woo’s Mission Impossible 2.

- The South Park scene: Several staff members were fans of South Park, so Tsurumaki let them put in a 20-second scene animated in its signature style. Personally, I love that a show influenced by western animation, itself influenced western animation (Avatar, Teen Titans, Steven Universe, etc., as stated earlier). It’s come full-circle.

- Episode three animation director Tadashi Hiramatsu was a big fan of Ninamori, so he made sure in each episode, even after becoming a side character, she would have a new hairstyle and outfit. She is the only character treated like this.

Just a few of Ninamori’s various appearances.

- Hiroyuki Imaishi asked Tsurumaki personally to let him handle the key animation for the action sequences in this episode. Imaishi’s signature energy and explosivity can also be seen in: Gurren Lagann, Kill la Kill, Little Witch Academia, Panty & Stocking with Garterbelt, and Space Patrol Luluco, among many other works. He went on to co-found the popular Studio Trigger in 2011.

- Naota’s now presumptuous attitude with Mamimi, who no longer likes him, is highlighted when he drags her off to Cafe Bleu, which has a storefront that was purposefully modeled after a love hotel.

- A reference to the “magical girl” anime genre is made when Haruko chants “Furi kuri furi kura furi kuri furi kura” while waving her guitar and producing glitter and sparkles in front of Amarao.

- When Haruko sky-surfs on her flying guitar while wearing a bunny suit, this is a reference to the Daicon III and IV Opening Animations, two short anime projects made by the founders of Gainax in 1981 and 1983; respectively, for the 1981 Daicon III and 1983 Daicon IV Nihon SF Taikai conventions.

Left: FLCL. Right: Daicon.

- When deciding what guitar model to assign to the character of the Pirate King Atomsk, Tsurumaki discussed it with Hiroaki Sakurai (director of Di Gi Charat, Cromartie High School, and The Disastrous Life of Saiki K.), a guitar fanatic and collector who is often seen walking around with a ukulele in hand. They eventually decided on the rare 1961 model cherry red Gibson EB-0 bass guitar.

The Gibson EB-0 bass guitar.

EPISODE 6 – “FURI KURA” / “FLCLIMAX”

- Atomsk’s name comes from the cold war spy novel titled Atomsk, written by science fiction author Paul Linebarger, using the pseudonym “Carmichael Smith.” To be clear, Tsurumaki didn’t actually read the novel; he just thought the name was cool.

- There is another black & white manga dinner sequence in this episode, even though Tsurumaki was asked not to do another one. But again, he insisted on its inclusion. In this one, as it goes on, less and less ink is used, and by the end, the drawings are done roughly in pencil, as if the manga artist was up against a deadline and was getting lazier and lazier. This may reflect FLCL’s production, as the schedule was “very tight at the end. Episode six was delayed a month.”

- Why does Haruko’s bracelet look like a handcuff with a single, sometimes animated chain link, and why does Atomsk have a similar chain link on his nose?

Left: Haruko’s chain link. Right: Atomsk’s chain link.

Well, as related by Tsurumaki, this is a remnant of a scrapped plot idea. Originally, Haruko and Atomsk were intended to be lovers (as Amarao wrongly suggests in the finished episode). Haruko was a space police officer and Atomsk, the Pirate King, was the wanted criminal in her custody, and they were having a forbidden love affair. While under arrest, Atomsk and Haruko were able to be together due to the handcuffs linking them. But, they were separated by Medical Mechanica, who kidnapped Atomsk, breaking their chain link.

- In the finished plot, Atomsk turns out to be a feral entity whose power Haruko is after. Of course, many traces of the original storyline still exist in the finished show, including Haruko’s handcuff-like bracelet.

- The giant hand was modeled after Tsurumaki’s real right hand.

- Atomsk’s symbol, which periodically appears on Canti’s screen, is the Japanese word for “adult”: 大人 (“otona”) but written upside-down and stylized to form a logo.

Left: Atomsk’s symbol on his beak. Right: Atomsk’s symbol on Canti’s screen.

- Twice in this episode, Haruko tells Naota, “You know, you’re still a kid.” The first time, when she’s sitting on his bed with him, it’s because he is still trying to be an adult with her; so she tells Naota that he doesn’t have to be–in Tsurumaki’s words, “he doesn’t have to worry about that stuff yet.” The second time Haruko says this to him, right before she leaves the earth, it’s to acknowledge that now, after all this time, Naota is finally acting like a kid. In that way, he finally grew up.

- As Tsurumaki puts it, “Kids who act like kids, and don’t pretend to be adults, are actually more adult.”

While I believe it’s debatable whether puberty, specifically, is a major theme of FLCL, I think it’s unambiguous that “adulthood” is. Here are a few more quotes from Tsurumaki on that theme (these were taken from the “Afterword” section of FLCL light novel 02):

“I don’t believe all children will become grown-ups. They may get older, get taller, pay taxes, and get married, but there are people who will never become grown up.”

“According to [Japanese] law, you’re considered a grown-up as soon as you turn twenty, but this isn’t the case. When I turned twenty, I was still in front of the television, critically hitting Metal Slimes in the Dragon Quest I’d bought at a used game store, and resetting when I got frustrated. A real grown-up wouldn’t have reset…Grown-ups…don’t have the luxury of resetting as they walk through life.”

“Even if we were to talk about economics, we’d still be kids.”

Amidst the outward randomness of FLCL, I love how thought-out and unified the show secretly is. On first viewing, I [and many people] thought it was just bizarre and illogical. On second viewing, I began noticing the subtleties and tenderness taken in developing the characters, as well as the above-average animation. On third viewing, I finally understood the plot, as well as the themes Tsurumaki and his team were trying to convey. It’s one of the shortest stints in anime, but I think it’s also one of the best. And I believe it’s too often written off as weird and nonsensical, and nothing else.

There’s a common saying that “every movie is a miracle–the fact that it got made.” No truer is that statement for me, than for FLCL. In doing the research for this essay, I found the more I learned, the more I realized that half of this show is a random amalgamation of things Tsurumaki liked, things he noticed in his daily life, and spur-of-the-moment decisions. Yet the show still comes together in a (debatably) cohesive manner.

Of course, there is a lot of deliberate randomness in FLCL, but even at its worst, it has some of the most creativity of any modern-era anime. Each episode houses a complete, satisfying character arc with a story that meaningfully continues into each following episode–there are no inconsequential scenarios. In episode one, Naota learns to face his vulnerabilities. In episode two, he learns to be there for others. In episode three, Ninamori takes the spotlight to learn to stop lying to herself, while hinting at this lesson to Naota. In episode four, Naota learns to not be afraid of failure, and that it’s okay to ask others for help. In episode five, he learns to not get full of himself. In episode six, he finally learns to stop being aloof, be honest to his feelings, and stop trying to be an adult.

I’d like to leave off with one more quote (from the 2010 MyNavi News interview):

Q: “FLCL is a piece of work that asks the question ‘what does it mean to become an adult?’–ten years later, have you found the answer?”

Tsurumaki: “Oh no, I really don’t know. It’s the same now as it was back then–I still don’t know… But I’ll start off by saying…”

“‘Let us all become children.’”

Agreed.

.

.

.

.

Sources & Further Reading/Viewing:

- FLCL Volume 01 (Light Novel) by Yoji Enokido – Commentary Section w/ Hiroki Sato (Fooly Cooly Producer). https://archive.org/details/manga_FLCL

- FLCL Volume 02 (Light Novel) by Yoji Enokido – Commentary Section w/ Kazuya Tsurumaki (Fooly Cooly Director/Producer). https://archive.org/details/manga_FLCL

- FLCL Volume 03 (Light Novel) by Yoji Enokido – Afterword with Yoji Enokido. https://archive.org/details/manga_FLCL

- FLCL DVD Director’s Commentary. https://www.amazon.com/FLCL-Complete-Blu-ray-Kari-Wahlgren/dp/B004DMIIPA/ref=tmm_blu_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

- FLCL World (Fan site) – History Page. https://web.archive.org/web/20090130103639/http://flclw.com:80/history

- FLCL World – Interview with Tsurumaki (Fan Questions at Otakon 2001 panel). https://web.archive.org/web/20080510144535/http://www.flclw.com/history/interview-with-kazuya-tsurumaki/

- Anime Expo Interview with Tsurumaki and Mayumi Shintani by Guardian Enzo for Lost in Anime – July 2016. http://lostinanime.com/2016/07/anime-expo-lia-exclusive-flcl-interview-tsurumaki-kaziya-shintani-mayumi/

- Interview with Tsurumaki by MyNavi News from October 16, 2010. https://news.mynavi.jp/article/20101016-flcl/

- “FLCL is the Formula” by Carl Gustav Horn for PULP: The Manga Magazine, including an interview with Kazuya Tsurumaki – June 2002. https://web.archive.org/web/20060508105558/http://www.pulp-mag.com/archives/6.03/flcl.shtml

- Crunchyroll “Feature Creative Spotlight: Kazuya Tsurumaki” by B. Teteruck. http://www.crunchyroll.com/anime-feature/2017/04/03-1/feature-creative-spotlight-kazuya-tsurumaki

- August 2003 Cartoon Network Ratings Report. https://web.archive.org/web/20120427010129/http://www.timewarner.com/newsroom/press-releases/2003/08/Cartoon_Network_Takes_Prime_Total_Day_Crown_for_Kids_211_Kids_611_08-12-2003.php

[I updated this essay Aug. 24, 2018 to add in-text links to the sources]