We only have one month left until the Chainsaw Man anime begins its broadcast, and like most people, I think it looks super promising. One glance at my recent Twitter or Instagram art posts will show you that I’ve been obsessed with the series. The trailers for the anime adaptation look beyond amazing, and the cast and crew behind it seem to be a healthy balance of all-star veterans and skilled up-and-comers. Make no mistake, I am really excited for this anime.

But I’m also keenly aware that I may be overhyping it. Well, not just me, but like, all of us.

This might be the most anticipated anime series of all time, just judging from the views that the trailers are amassing across Youtube, and the constant chatter across the internet. Either way, it’s safe to say a lot of people are looking forward to this show, and the fans who have already read the manga can’t stop talking about it (like me). That’s why I want to spend some time today, before the anime premieres in October, to ground everybody—especially those going in blind.

Let’s talk about why Chainsaw Man is popular, what you should expect from it, and why it may not meet your hype.

(No spoilers in this article, but external links may contain spoilers)

First Things First…

Let’s get this out of the way first. Chainsaw Man is NOT “peak fiction.” Chainsaw Man will NOT be the anime that “saves anime.” It will not be the best anime of all time nor even make it in your top three. Or your top five. It may not even be in your top ten when all is said and done. I mean, it might for some people. It might for me. It might for you… but just to be safe, since I don’t know you, I’ll just say it will probably not.

There. Hype, grounded. But let’s talk more specifics…

So, why is Chainsaw Man so popular? Reception from critics appears to be almost unanimously positive, and its sales numbers continue to skyrocket long after the series’ first “part” ended. It’s a rare manga series that has amassed such a large following that it’s already become a massive cultural phenomenon long before its anime adaptation has premiered. In fact, The New York Times and Paste Magazine even have the anime on their “Top Fall 2022 TV shows to Watch” lists (and it’s the only Japanese show on the Times list).

The Title Sells It

One reason for its ubiquity may be its simple title: Chainsaw Man. It’s extremely evocative, descriptive, and catchy. It immediately conjures up images of a grindhouse B-movie or perhaps a dark superhero. It sounds ridiculous but also scary. When people hear the title “Chainsaw Man” and see a picture of the main protagonist with chainsaws coming out of his head and arms, it totally clicks. There’s an immediate understanding of the kind of story it might be, which creates a sense of anticipation.

In comparison, let’s talk about, say, One Piece. I love this series too, but admittedly the title does not really clue you in to anything about the story. That makes it harder to drum up hype for new potential fans, since you have to do more explaining. It’s part of the reason why Demon Slayer I think has become so popular – the title itself sells it.

The Jujutsu Kaisen Effect

It probably is also a benefit to Chainsaw Man that the studio behind it, MAPPA, made Jujutsu Kaisen. Before it was adapted to animation, the manga of Jujutsu Kaisen had no more than a cult following among the people who were reading Shonen Jump at the time. But, since the anime started airing, and the movie Jujutsu Kaisen 0 came out, the franchise has blown up in popularity and people everywhere are eagerly awaiting the sequel seasons. In the meantime, fans are now extra hungry for shows that are similar, especially if they’re from the same studio, and the same magazine.

And it’s hard not to make comparisons between Jujutsu Kaisen and Chainsaw Man, especially after Chainsaw Man’s creator Tatsuki Fujimoto admitted it himself. They’re both about a teenage boy who joins an organization in modern day Tokyo to exterminate monsters born from human emotions that roam the streets, after becoming part-monster himself. Both series are action-oriented, but also feature good comedy and drama. In general, I feel like the vibe of these two shows are pretty similar, too. Chances are, if you like one of them, you’ll like the other.

That said, if you’ve seen Jujutsu Kaisen and didn’t like it, I would not discount Chainsaw Man just yet. I’ve watched Jujutsu Kaisen—both the show and the movie—and I’ve read over a hundred chapters of the manga. And to be frank, while I think some of the characters are great (Nobara, Maki, and Yuta, namely) and the action is awesome, the way the story is written and paced overall is not my cup of tea, and I don’t love its overly complicated exposition dumps, either. Chainsaw Man, on the other hand, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed both times I read it. It also has pretty great, unique characters; the campy yet often poignant writing and brisk pacing of the story is much more my cup of tea; and its world feels far simpler and more cohesive to me. That said, it’s not perfect.

It Didn’t Meet My Expectations

While I can boast that I read the manga before the anime came out, I definitely am not an OG. Chainsaw Man’s original run in Weekly Shonen Jump magazine was from December 3, 2018 to December 14, 2020—the same day the anime was announced. And by then, I hadn’t read it yet. I tried earlier, but after the first few chapters, I found I wasn’t interested. Little did I know, Chainsaw Man is one of those series that takes a second to get going, but when it does, it only gets better and better—in fact, if I were to rank my favorite story arcs in the series, the list would basically be in reverse-chronological order.

That’s probably why the hype surrounding Chainsaw Man after it ended was difficult to escape, with readers high on arguably the best story arc in the series. And I have to admit, every time I stopped by my local Kinokuniya bookstore, the brightly-colored covers of the Japanese tankobon volumes were always so alluring.

The curiosity-laden hype built up in me so much that when MAPPA held their 10th anniversary stage show livestream on June 27th, 2021, I willingly stayed up until 4:00 A.M. to watch their Chainsaw Man panel where the first teaser trailer was revealed. And, like everyone else who saw it that early summer morning, I was totally blown away. Even though I was expecting something good, I didn’t think it would be that good—from the gorgeous compositing and the highly-detailed drawings to the obvious JJK-influenced sakuga action, along with a score composed by Kensuke Ushio, there was nothing more they could have done. It didn’t matter that I hadn’t read the manga yet; MAPPA made a trailer so jaw-dropping it would get every anime fan in the world excited.

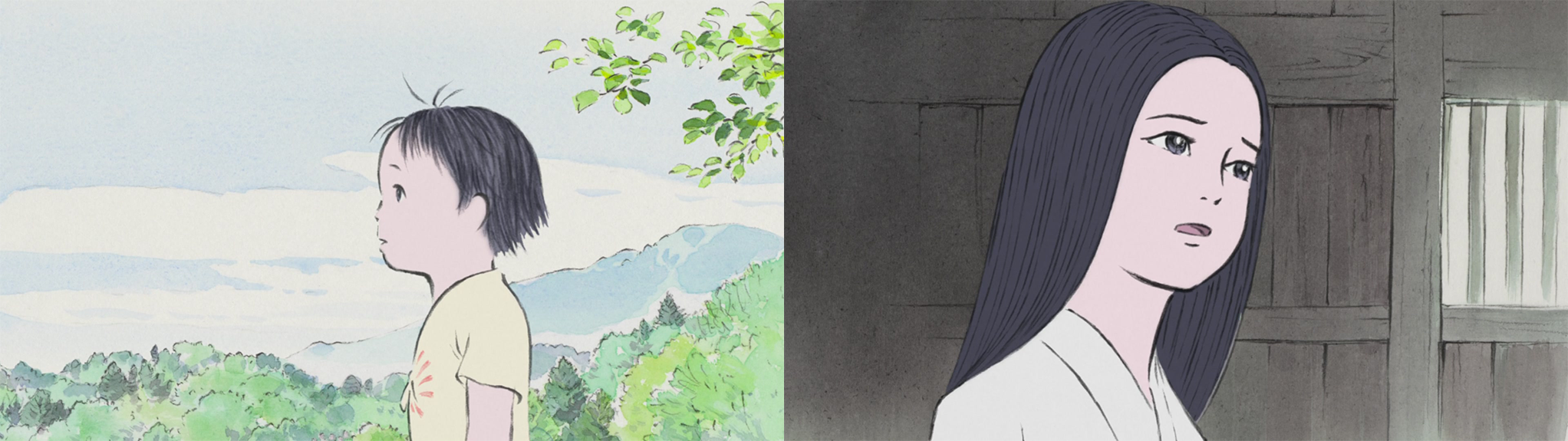

Not long after that, Tatsuki Fujimoto released his first post-Chainsaw Man manga, and I made my first foray into his work. Look Back, a 140-page standalone one shot, was released on July 19, 2021, and out of curiosity, I decided to read it. It tells the story of two girls who meet in elementary school and grow up to become a manga artist duo.

If you’ve read it, it’s probably no surprise to you that I was, well, surprised. The author of one of the most popular modern shonen battle manga went and wrote a down-to-earth tragic human drama? And one that was so cinematic, so sensitive, so inventive, and so specific?

Needless to say, this changed my impression of who Tatsuki Fujimoto was and what Chainsaw Man might be. I was excited for the anime, but now my desire to jump ahead and read the manga increased tenfold. In September 2021, on my next stop to Kinokuniya, I finally broke down and picked up the first volume. That was a mistake.

I read that first volume in a flash, and realized I was so hooked that I wanted to read more ASAP. And I probably could have just paid the two bucks for Viz Media’s Shonen Jump app and binged the whole thing in a day, but I started it in Japanese, and I wanted to continue in Japanese.

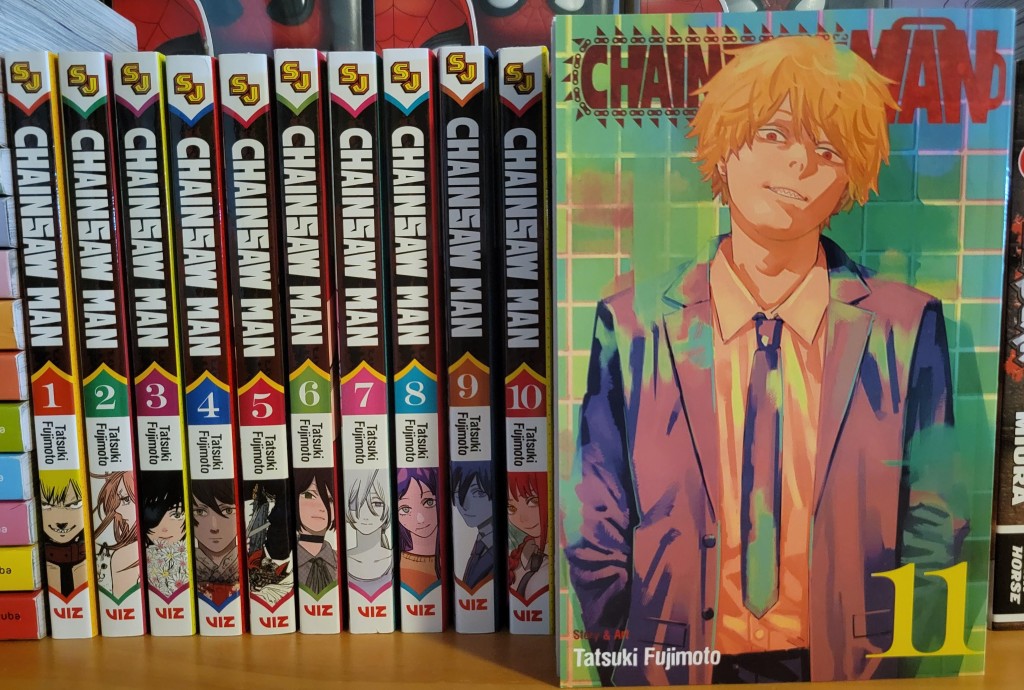

Long story short, I eventually ordered the entire 11-volume set on Amazon JP (which ended up being a bad decision because it was delayed in the mail and I had to wait 2 agonizing weeks for it to arrive and I could have totally just bought it all at my local Kinokuniya, but ANYWAY). After I received the books, I read the entire thing within a week, which is probably the fastest I have ever read a manga series in Japanese. And that’s both a testament to how much I’ve improved in my Japanese studies, but more importantly–how engaging Chainsaw Man was for me—I just couldn’t put it down.

At the same time though, I’m not sure if it totally met my high expectations. In my notes for the series, which I jotted down as soon as I finished it, I wrote: “Was it as good as it was hyped up to be? Nah, but it was very enjoyable.” Just like any other series, there are highs and lows.

Again, I think Chainsaw Man gets better and better as it goes along, and on top of that, it also rewards repeat read-throughs. There are legitimately parts of the story now that move me to tears. At first glance, the series seems like an over-the-top, always-at-11, shonen action gorefest, and it definitely is that at times. But it’s also quiet when it wants to be, poignant, and touches on themes that I’ve never seen another shonen manga address to the same degree—stuff like, the price of happiness and comfort, the consequences of ignorance, the fear of manipulation, and the complexity of love.

But when the anime starts up, I wouldn’t be surprised if a lot of people think the early episodes are nothing special or that it’s “not as good as Jujutsu Kaisen” or whatever. For me, Chainsaw Man’s first great arc starts just a bit before the halfway point of the story. And I think most fans will agree that the last third of the story (volumes 8-11) are an almost-nonstop high. Before that, it’s still good stuff, but admittedly I don’t know if I would put it that far above Demon Slayer or Jujutsu Kaisen. If we only get one cour’s worth of episodes for the anime’s first season, Chainsaw Man may not truly “pop off” for first-time viewers until the end.

Originally Unoriginal

So what should you expect? And how does it differentiate itself from other Shonen Jump shows like Demon Slayer or Jujutsu Kaisen?

To answer the first question, it may be helpful to compare Chainsaw Man to some more shows. I’ll just quote Fujimoto himself:

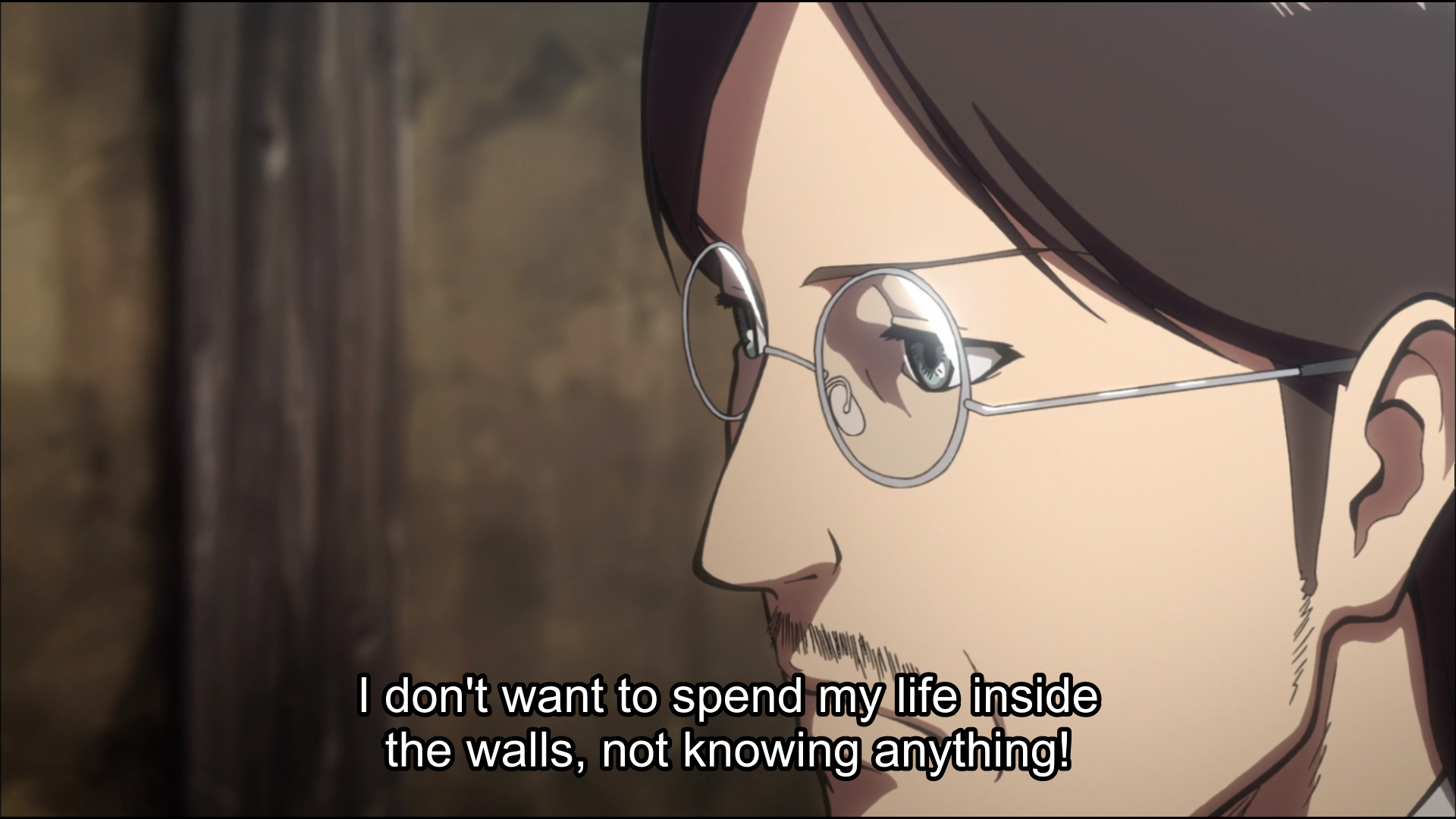

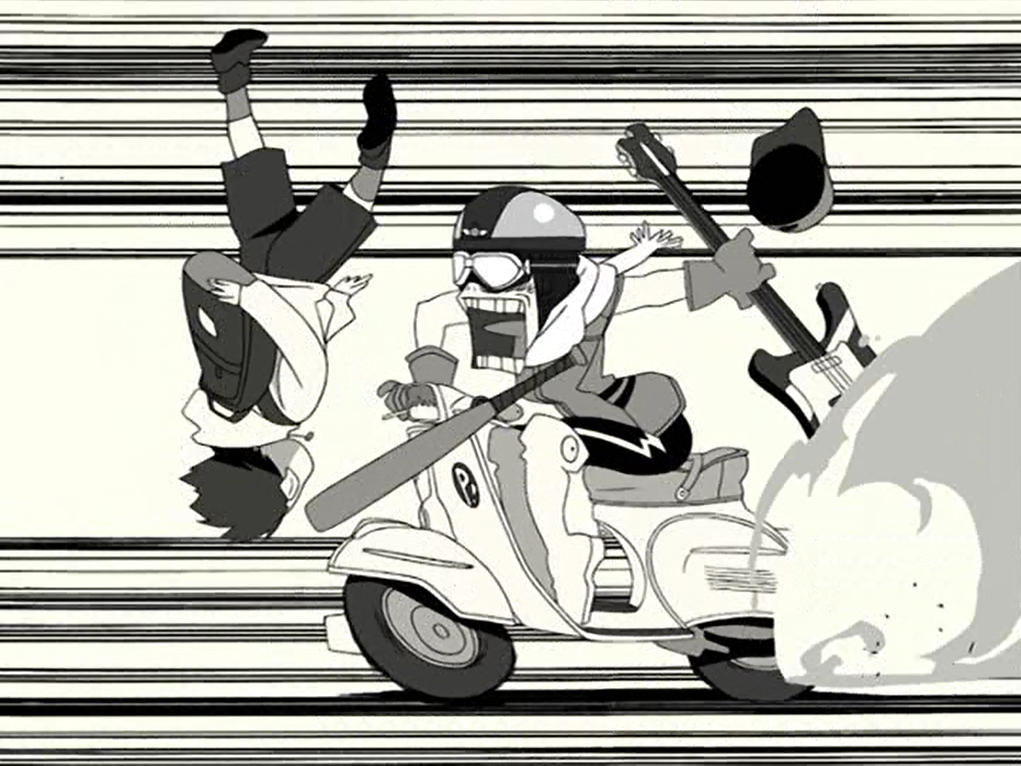

“I drew Chainsaw Man with the intention of making a wicked FLCL or pop Abara.”

“Chainsaw Man is like a copy of Dorohedoro and Jujutsu Kaisen; and the animation studio behind Dorohedoro and Jujutsu Kaisen is making the anime!? There’s nothing left for me to say!! I’m looking forward to it!!

So yeah, Chainsaw Man unabashedly takes cues and inspirations from various media that have come before it; and it’s not just limited to anime and manga. It doesn’t take a detective to figure out that Tatsuki Fujimoto is a massive cinephile, as every volume of Chainsaw Man has a comment from him declaring his love for movies like Hereditary, Get Out, Death Proof, and Coraline, among others. Plus, almost every manga he’s written, from Fire Punch to Chainsaw Man to Goodbye Eri, has at least one scene with characters either making a movie, going to a movie theater, or discussing movies. Fire Punch in particular is filled with blatant movie references, and Goodbye Eri is all about someone making a movie.

Chainsaw Man is a little more subtle about it, but its film influences are still evident. The title of the series itself was inspired by the classic slasher film The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and in general the series has a similar vibe of a schlocky exploitation film, at times. As a storyboard artist, I also find Fujimoto’s panel layouts very interesting because they often evoke, well, cinematic storyboards. One of his trademarks is drawing the same panel composition multiple times in a row to show a progression of action and/or subtle character expression within the same shot. Goodbye Eri, in particular, does this throughout, and with the way most of the panels are the same shape and size, it basically is a storyboard for a film.

But, Fujimoto is a manga artist after all, so Chainsaw Man possibly borrows more from anime and manga than it does from live action media. For Chainsaw Man, Fujimoto has referenced or cited influence from The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya, Jin-Roh: the Wolf Brigade, Junji Ito’s works, Daisuke Igarashi’s works, Berserk, Hunter x Hunter, Gunbuster, the Kizumonogatari films, and even his own previous works.

Also, although I haven’t found anything concrete to suggest that Chainsaw Man was inspired by Go Nagai’s classic manga Devilman, it’s hard to believe it wasn’t. Both manga are gruesome tales about a teenage boy who becomes a devil-human hybrid and uses that power to defeat devils. Also, coincidentally, the musical composer for the Chainsaw Man anime, Kensuke Ushio, also composed the music for Devilman Crybaby—the 2018 anime retelling of the 1970s series.

Not Jump-Like

And perhaps precisely because Fujimoto is aware of all his influences, he’s able to break away from established tropes, especially those found within the shonen genre. Chainsaw Man is often described as a “not Jump-like” Jump manga, and part of that has to do with the significant amount of gore and bloodshed, and its abnormally mature brand of sexual content in a manga magazine intended for pre-teens. But, the key aspect of Chainsaw Man that differentiates it from other Jump series is its protagonist, Denji.

You may have heard the three guiding principles of Shonen Jump before:

FRIENDSHIP!

EFFORT!

VICTORY!

These are the themes that define most of the manga that grace the pages of the magazine, and that shouldn’t come as a surprise, since Jump targets young, impressionable tween boys. As a result of that, many of Shonen Jump’s main heroes act as role models for readers. Think of characters like Son Goku, Monkey D. Luffy, Naruto Uzumaki, Ichigo Kurosaki, Tanjiro Kamado, Izuku Midoriya, and Yuji Itadori. Many of them have big dreams, a love for their friends and family, the desire to work hard, and/or an unbreakable moral code and sense of justice. Several of them are also pure of heart, exceedingly kind and earnest, and even have above-average emotional intelligence and empathy for others.

Denji is, uh, not like that. Not that he’s an asshole, either. He’s just a kid who was dealt a terrible hand in life, wallowing in endless debt, hunger, and poverty. He has no big dreams or goals because all he can think about is how to feed himself (and his dog Pochita). His biggest aspirations include one day eating toast with jam on it. He doesn’t have an unconditional love for his friends or family because he has none. He works hard, but not in order to better himself as a person, but because he simply needs to, in order to survive. He doesn’t care about anyone but himself. He’s a simple guy—he doesn’t even know how to make friends, much less get a girl to like him, but he still dreams about one day touching some boobs and getting a kiss.

Yeah, Denji is not a role model for readers to look up to; apart from his poor life circumstances, he’s just an average, horny teenage boy. But in that way, he might be more relatable to most people than the other Shonen Jump heroes. He’s not necessarily a better-written character than Tanjiro, Izuku, or Yuji, but he’s a welcome change of pace from that established norm of the altruistic, selfless hero. Role model-type protagonists are always good to have, but sometimes they can feel like an unattainable standard for people to live up to in real life. Characters like Denji show us that it’s okay to be yourself. And he’s probably the biggest reason that loyal readers of Shonen Jump have gravitated so much to Chainsaw Man as a breath of fresh air.

Actually, scratch that. Power is the reason. Or maybe Makima. Or Reze? Kobeni? Aki? Pochita? There’s actually a lot of surprisingly good characters in Chainsaw Man. Look forward to meeting all of them!

The Indie Filmmaker

But another aspect of Chainsaw Man that I almost overlooked was how weird it is. If you’ve read enough of his work, you’ll know that Tatsuki Fujimoto loves surprises. He loves catching readers off-guard and playing UNO reverse cards (or whatever the literary equivalent of that is). Fire Punch is a series that takes so many weird left turns that it’s impossible to predict what will happen next as you’re reading it, for better or for worse. Chainsaw Man is a more refined version of that, but it’s not afraid to still get weird sometimes.

A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to attend an anime convention with someone who had never read Chainsaw Man, and it made me realize how many inside jokes and strange things that don’t make sense out of context there are. Obviously, there were a lot of Chainsaw Man cosplayers there, and most of them wore the standard outfits and looks of the characters from the anime trailers. But how could I explain to him why there was a Power cosplayer with extra big horns? Why was there someone dressed as a car? Why is there a girl with an atomic missile for a head? Why are people repeatedly saying the word “Halloween”? Why are people barking like dogs?

All good questions!

For sure, Chainsaw Man is a bit weird. Fujimoto has a different way of thinking and approaching manga creation than his peers in Jump. In fact, if you’ve read his one-shots like Goodbye Eri or Look Back, or his previous series Fire Punch, he may not strike you as the kind of guy who would be interested in writing a standard mainstream-style shonen battle manga like Chainsaw Man. In a sense, Chainsaw Man itself feels like a bit of an outlier within Fujimoto’s bibliography, which is full of weird, mature, experimental manga telling stories about broken people with messy feelings. It may surprise you that a guy like him had always dreamt of making a manga for Shonen Jump, because he apparently did.

It’s like if an indie auteur filmmaker on the fringes of the industry pitched a superhero movie to a big Hollywood studio, somehow got it funded, and ended up making one of the most critically acclaimed AND most financially successful movies the genre had to offer—all without compromising on his unique style and vision.

‘Concise’-saw Man

Another key aspect of Chainsaw Man that differentiates itself from most of its shonen manga compatriots, and is probably one of the most appealing aspects of it—is that it tells a complete story in just 11 volumes.

For reference:

Jujutsu Kaisen: 20 volumes (and counting)

Demon Slayer: 23 volumes

My Hero Academia: 35 volumes (and counting)

Dragon Ball: 42 volumes

Naruto: 72 volumes

Bleach: 74 volumes

One Piece: 103 volumes (and counting)

Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure (all parts): 131 volumes (and counting)

Shonen Jump manga have a reputation for going on for years and years, volume after volume, and telling stories that span hundreds of chapters and tens of volumes. It’s no surprise many people find some of them daunting to get into. And although the story of Chainsaw Man is technically continuing past its 11th volume in a so-called “Chainsaw Man Part 2,” I don’t think any fans of the series would have been disappointed if the series had ended with “Part 1.” It tells a complete story that resolves all of the important plot threads and character arcs that had been set up from the beginning with an epic, emotional conclusion—and it falls in at just 97 chapters. With the pacing of an anime series, the entirety of that story would be easily covered in a standard two-cour season of television.

For comparison, the manga Your lie in April, which was also 11 volumes in total, was adapted completely into a very well-paced 22-episode anime series. So, I think Chainsaw Man (Part 1) could quite comfortably be adapted in a standard 26 episodes or less.

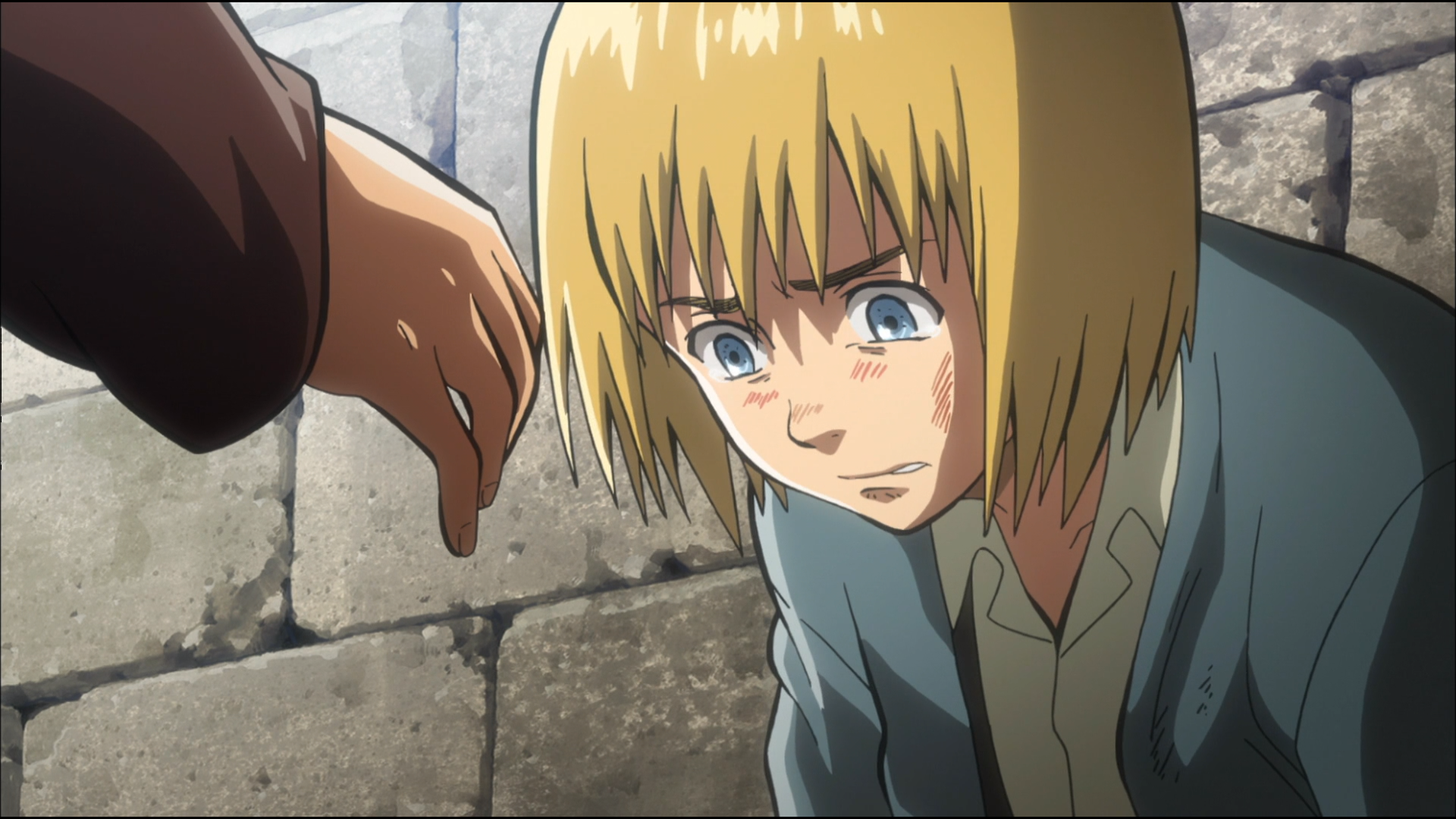

The question is, how much of the story are they adapting for this first season starting in October? The whole thing? Just half? Many anime debut with just a single cour—that is, 12-13 episodes. And once the anime takes off, more seasons are announced. That’s what happened with My Hero Academia, for example. And considering how high the production quality appears to be on Chainsaw Man, I would not be surprised if they only have time to make one cour for now—likely covering everything from the Introduction Arc to the Bomb Arc. MAPPA’s final seasons of Attack On Titan have also both been about 1 cour in length (Part 1 was 16 episodes, and Part 2, which aired 10 months later, was a standard 12).

At the same time though, MAPPA’s current Shonen Jump darling Jujutsu Kaisen got a full 24-episode first season right off the bat with only a 2 week break in between cours, due to the winter holidays. And considering the MAPPA staff’s seeming openness to mention Chainsaw Man’s later story arcs in interviews, and even express their interest in adapting the manga’s currently ongoing “Part 2,” perhaps a full 24-26-episode complete adaptation of Chainsaw Man Part 1 with no (long) breaks in the middle, is what MAPPA is preparing for us.

Another option is to go the Spy x Family route, where one 25-episode season is being split in the middle by a 3-month break, though that isn’t common.

In any case, I’m just speculating at this point, so let’s move on.

Stay Grounded

I almost forgot that the title of this (very disorganized) article is “Chainsaw Man – Are We Overhyping It?,” and I haven’t really gotten to the grounding-your-expectations part yet. In fact, just by rambling on about Chainsaw Man for so long, I probably only increased your hype for it.

Let’s be honest here. It’s just a shonen at the end of the day. Yes, it’s a little more out-there than your average shonen, but maybe you’re someone who loves the standard formulas of shonen manga, and the ways Chainsaw Man differs won’t be to your liking. Maybe its weirdness will, uh, weird you out. Maybe you’ll find Denji or the other characters annoying or unlikeable. Maybe the relatively short length of the story will cause you to feel less invested.

On the other hand, perhaps you’re sick and tired of shonen tropes, but the ways Chainsaw Man tries to innovate won’t be enough to charm you. Maybe it will still feel too similar to Jujutsu Kaisen or Dorohedoro, or just feel too derivative of the media that inspired it in general.

And even if the manga is any good, what about the adaptation? The staff and cast seem great from top to bottom, with veterans and skilled up-and-coming artists alike. MAPPA also seems pretty confident in the production, considering that they are foregoing a production committee—a standard for most anime—and managing the animation, the promotional materials, and the merchandise all on their own. But will they really be able to meet fans’ massive expectations?

I will say, one worry I have about the trailers they have shown is that they don’t seem to touch on the comedic side of Chainsaw Man too much. That key aspect of Chainsaw Man feels missing. But perhaps it makes sense that they would want to focus on the impressive action sequences and dark setting in order to get people hyped. And it certainly looks impressive! The drawings have gotten more streamlined in the newest trailer compared to the original teaser from 2021, and the animation and compositing look absolutely feature-film level. At the same time, though, the desaturated colors in the latest trailer feel drab compared to the bright tones that Fujimoto uses in his color pages and volume covers. But again, maybe that’s just the way the trailer was designed.

Either way, the big question is whether they can actually maintain the degree of quality implied in the trailers throughout each episode over the entire series, and whether or not that ends up mattering either way. In any case, we won’t know until we see the full show once it starts airing in October.

The Future Rules!

If you held me at gun(devil)-point and asked me what I’m truly expecting from the Chainsaw Man anime, honestly, I’d have to admit I’m expecting something pretty amazing. Even as a grumpy ol’ jaded lifetime anime-enjoyer who’s been enjoying anime since Dragon Ball GT aired on Toonami and Yu-Gi-Oh! aired on KidsWB, I think we’re in for one of the most exciting shows in modern anime history.

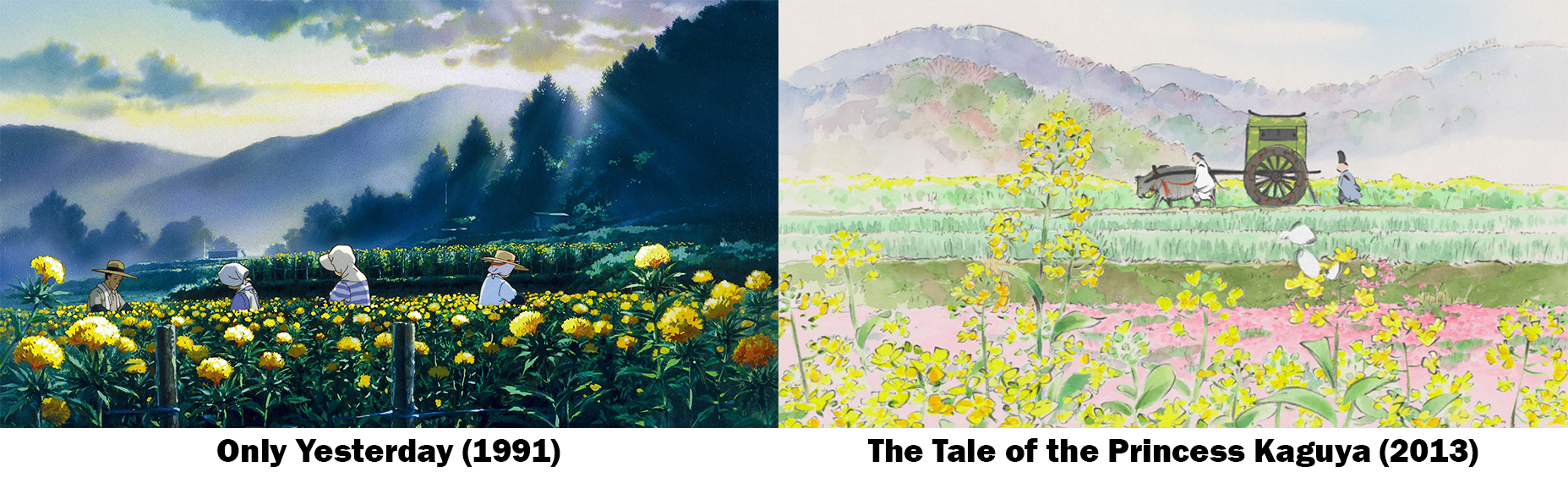

Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball Z were household names in the 90s. Shonen Jump’s One Piece, Naruto, and Bleach became the “Big Three” in the 2000s. The early 2010s ushered in a new era of dark shonen and isekai with Attack on Titan and Sword Art Online, respectively. The late 2010s welcomed in the comic-book inspired mainstream juggernauts One Punch Man and My Hero Academia. And the 2020s have already pushed anime more into the mainstream than ever before with hits like Demon Slayer and Jujutsu Kaisen (Not to mention Attack on Titan’s final seasons).

This October, whether you like it or not, amidst what is shaping up to be one of the best seasons of anime ever (Check out My Top 10 Anticipated Fall 2022 Anime), prepare to meet the new face of the anime world, as I think Chainsaw Man is poised to become one of the most culture-defining and influential shows of the decade to come.

…or I’m overhyping it.